By Christine Koporc MSc & Jennifer Kartley DVM

Heartworm disease is well known for affecting dogs, but its impact on cats raises many questions for pet owners. While the initial transmission is similar for both cats and dogs, when and how a cat progresses after exposure to a heartworm is drastically different than in dogs.

Let's explore one more way our feline patients are so different from their canine counterparts and dive into everything you need to know about heartworm in cats.

What Is Feline Heartworm? How Does It Differ from Heartworm in Dogs?

Heartworm disease in cats and dogs is caused by a parasitic worm called Dirofilaria immitis. It has been diagnosed around the world, affecting hundreds of thousands of pets each year. Once these larval worms are inside your pet's body they grow and develop over a period of time. They can infiltrate your pet’s heart, lungs, associated vessels, and tissues, causing organ damage, which can be fatal as they progress through their life cycle.

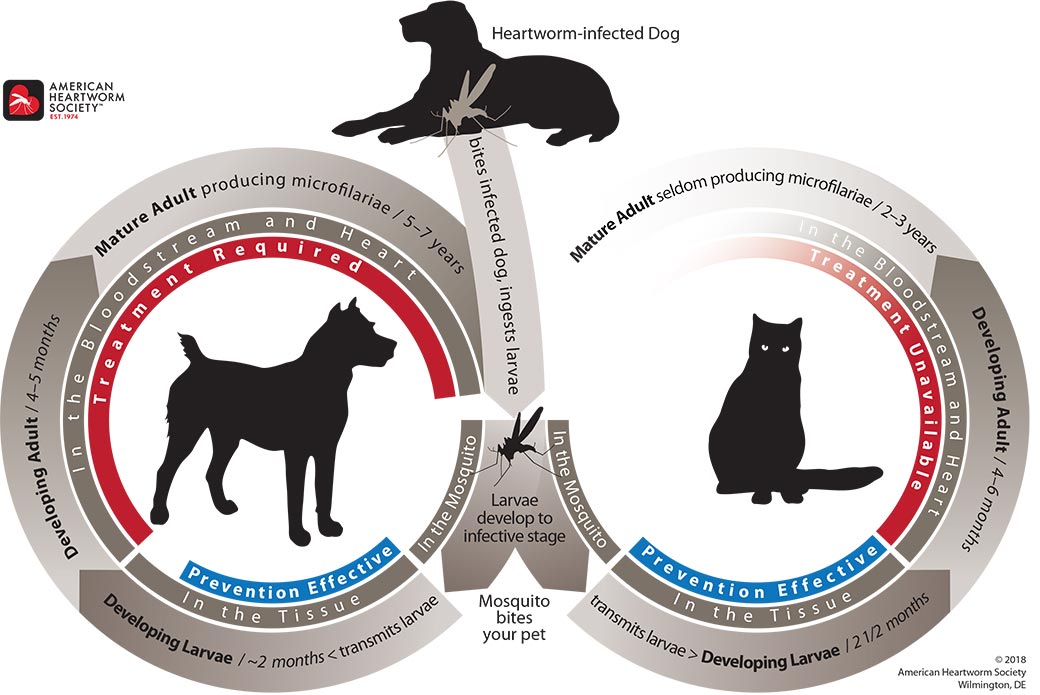

While both cats and dogs are susceptible to becoming infected with heartworms, cats are atypical hosts, meaning that heartworms progress and affect cats differently than dogs. Dogs are among the species that are considered natural heartworm hosts, meaning the worms thrive, grow to adulthood, and reproduce within a dog’s body. Cats, on the other hand, aren’t as favorable of a host, and heartworms struggle to survive in cats, causing them to often die off before reaching maturity and reproducing.

Because of the differences in worm survival between cats and dogs, cats typically harbor far fewer worms than their canine counterparts. In fact, while dogs can harbor dozens – if not hundreds – of adult worms with their organs, cats will only have a handful, if not just a single worm. However, this doesn’t mean that heartworm isn’t dangerous for cats.

Even if only a few worms are present, heartworms can cause a number of serious and life-threatening health complications in cats. Once infected, a cat’s immune system will aggressively attack the invading parasite, causing significant inflammation and damage to a cat’s organs and tissues. Cats can suffer from this inflammation and organ damage long after the worms have passed, making the effects of heartworm in cats long lasting and far-reaching.

Symptoms of Heartworm in Cats

When it comes to identifying heartworm in cats, there are a few signs pet owners should be on the lookout for, including:

- Coughing or wheezing – This can resemble asthma and is caused by inflammation in the lungs.

- Difficulty breathing – You might see your cat breathing more rapidly or more heavily than usual.

- Vomiting – Even if your cat hasn’t eaten anything unusual, persistent vomiting can be a sign.

- Lethargy or decreased activity – If your cat seems more tired than usual or is avoiding playtime, it could be a red flag.

- Weight loss – A gradual decline in weight can occur in some cases.

How Do Cats Get Heartworm?

Contrary to what some pet owners may assume, heartworm isn’t directly spread between dogs and cats. Instead, it’s transmitted by mosquitoes carrying the larval form of Dirofilaria immitis. In our area, common carriers include dogs, coyotes, and foxes, which serve as hosts for the parasite. These animals harbor adult heartworms that produce microscopic offspring called microfilaria, which circulate in the bloodstream.

When a mosquito bites an infected animal, it ingests these microfilariae. As the mosquito feeds again, it can deposit the larvae into a new host — whether that’s a dog, cat, or even wildlife. Because mosquitoes can enter homes, even indoor pets are at risk of exposure. You, me, your dog, or cat are all susceptible to a mosquito bite regardless of being inside or outside.

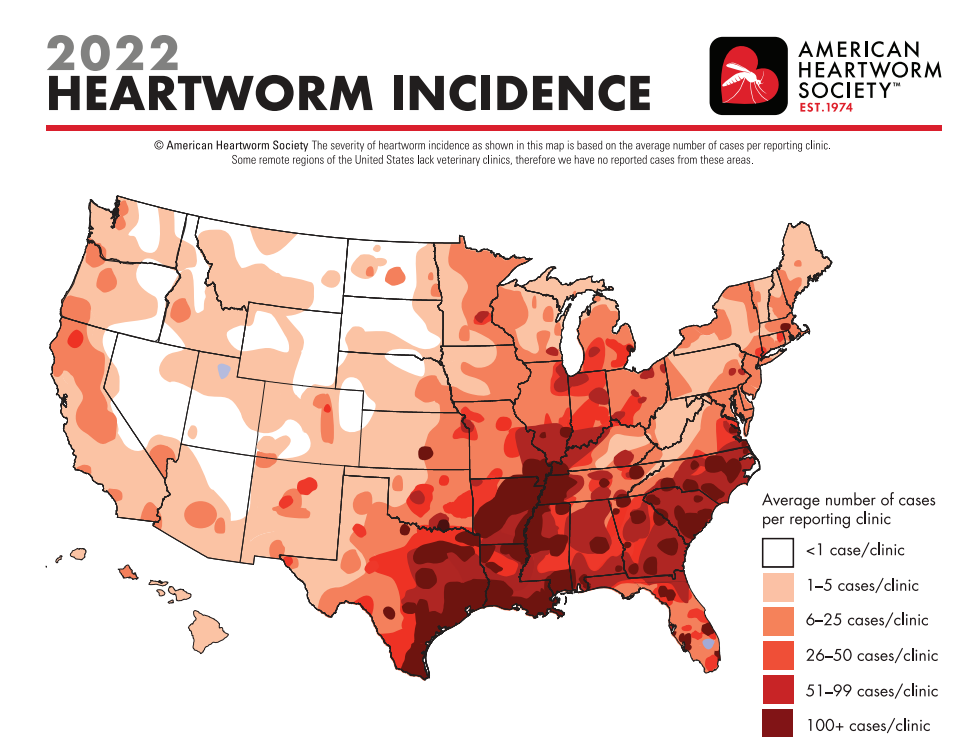

Hot Spots for Heartworm

In Northeast Ohio, we have established populations of wild coyotes that harbor microfilaria and, unfortunately, some neighborhood dogs. Urbanization and a multitude of factors contribute to sustaining populations of mosquitoes all year round. Pockets of areas with warmer temperatures, called heat islands, are found in suburbs and cities, which allow mosquitoes to prolong their duration of activity and reproduction, resulting in the further spread of this deadly parasite.

The Stages of Heartworm in Cats: How Feline Heartworm Progresses

Cats and how heartworm disease affects them is a complicated subject. The interaction between the cat and the progression of heartworm disease is completely different from a dog, as we discussed above. While cats are not the normal host for heartworm – neither are humans, thankfully – the initial infection can happen just as easily in felines. However, after the initial infection, cats differentiate themselves from dogs in how heartworm progresses and affects them. Although cats do not get as many worms per infection, there are still deadly side effects from being exposed to heartworms.

The American Heartworm Society's Feline Guidelines highlight two main stages of feline heartworm disease:

- Reactivity to the arrival of the heartworms to the lung tissue

- Reactivity to the death of adult heartworms later in the life-cycle

Unfortunately, both of these situations generally result in sudden pulmonary failure and often death. When heartworms arrive in the pulmonary artery (the artery or vessel where blood travels to the lungs to become oxygenated) and end up in lung tissue, a cat's reaction is similar to what asthma or allergic bronchitis looks like. If a cat does not react to the initial exposure to heartworms in the lungs, the parasite develops into an adult worm.

Unlike dogs, most cat immune systems do not allow the progression of the heartworms to this part of their life cycle. Because there is usually only one or two worms, and those worms are not typically able to reproduce, all that is left for them to do is mature and die. When a heartworm dies in your cat's body, the immune system overreacts, causing a sudden inflammatory response in the lungs, possibly causing thromboembolism, which is essentially a blood clot formed in the vessel. Unfortunately, these responses often lead to the death of the pet.

The Challenges of Diagnosing Heartworm Disease in Cats

Misunderstood testing guidelines for feline heartworm disease further complicate the topic of our discussion. Dogs have had specific recommendations for diagnosis with both point-of-care and reference laboratory testing. These testing options are available for cats but the results they yield in identifying heartworm in cats are not as reliable.

The main reason is that the progression of their infections is different from dogs, so the conditions that need to be met for a dog to show up positive are not met in cats. The most common testing for heartworm in dogs uses what is called antigen testing. In heartworm disease, the antigens produced by pregnant female worms are what we can detect. This means that in order for a test to show up positive with current testing techniques, we need at least four sexually active worms: one male and three female worms.

These standards don't look so good when it comes to our feline patients. Why? Well, they usually only get one or two worms. Remember, they are NOT the usual host for this parasite and often eliminate heartworm before they reach this adult stage. This complication is one of the reasons why it is hard to successfully diagnose heartworm disease in cats, given how current testing techniques are designed.

Treating Heartworm in Cats

The differences between heartworm in cats and dogs also extends to treatment options, with cats having far greater limitations. In dogs, veterinarians can utilize a series of injections of melarsomine as well as other medications to combat any existing bacteria or infections present as a result of the heartworm. However, there is no approved medication or injection available to eliminate heartworms in cats. Instead, cat heartworm treatment is typically supportive in nature and, instead of elimination of the worms, focuses on managing symptoms and reducing overall inflammation.

The drugs used to treat heartworm in dogs are not safe or approved for use in cats. If you suspect your cat has heartworm, it’s crucial to work closely with your veterinarian to safely manage your cat’s symptoms and keep them as comfortable as possible.

What You Need to Know About Cat Heartworm Prevention

Now, there is a positive surrounding feline heartworm disease: we can prevent it! Prescription medications are available that not only prevent heartworm infection in cats but also eliminate other intestinal and external parasites, including fleas and ticks. In the United States, heartworm prevention can only be prescribed by a licensed veterinarian who has seen the pet in the last 12 months.

Heartworm prevention in both dogs and cats are only effective at killing the worms at a certain stage in their life cycle, which is why giving it monthly is absolutely pertinent to its effectiveness and why missing a dose or two can be detrimental. Over the counter flea and tick preventatives purchased legally do not contain heartworm prevention. Applying a monthly preventive will promote the longevity and quality of life for your cat by ensuring they are not subject to the easily preventable and often fatal health concerns we have here in Northeast Ohio.

In the United States, heartworm is now considered endemic to all 48 contiguous states as well as Hawaii. Dogs and cats can both suffer from this preventable disease, but monthly medication prevents infection when they are exposed. The American Heartworm Society is continually reviewing the newest information regarding heartworm disease in cats and publishing updates since so much is still not defined in how this disease process affects feline patients. Remember, there is no approved treatment for feline heartworm disease. The only way to prevent it is to give your cat a monthly preventive medication prescribed by your veterinarian.

If you have questions and you'd like to reach out to us, you can call us directly at (330) 562-5100, or you can email us at [email protected]. Don't forget to follow us on social media Facebook, Instagram.